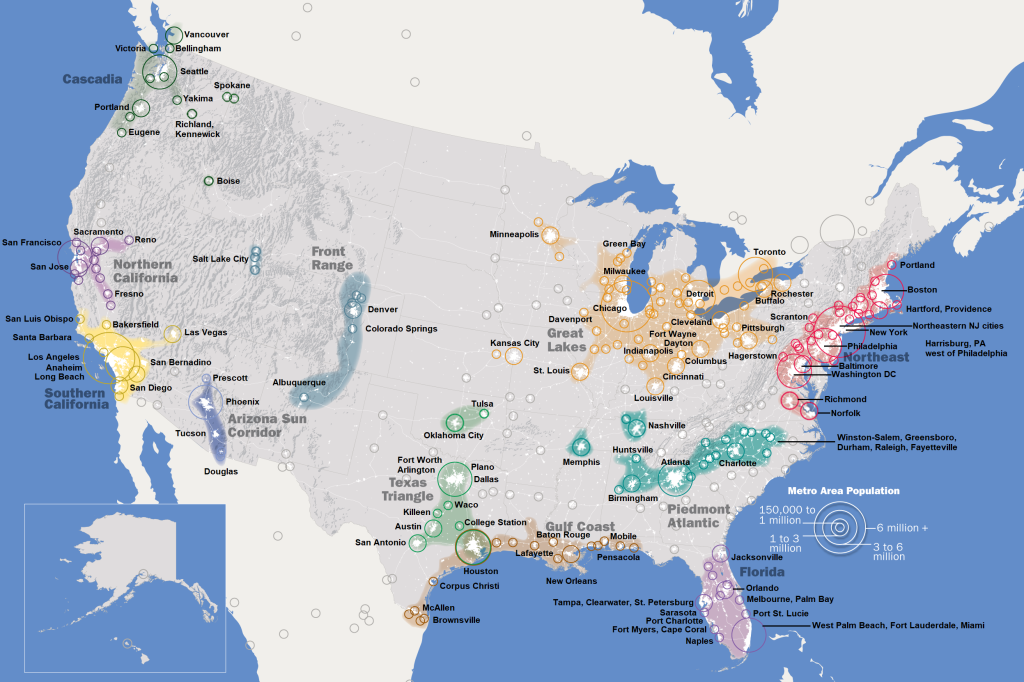

In Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America, Alec MacGillis notes that the city at the center of a circle containing the largest population within a one-day drive is Dayton, Ohio. You can kinda see that in the map above, which I discovered through Brilliant Maps. They got it from the highly precient Defining US Megaregions, published by the Regional Plan Association in 2009, long before interstate highways across the US became flanked by transport transfer buildings big enough hold five Costcos, and trucks hadn’t yet threatened to outnumber cars on major highways.

When we got a place in Bloomington four years ago, we thought the town was basically isolated. But we quickly found that we were kinda close to a mess of major league cities. Indianapolis is closest, less than an hour up I-69. Louisville is a bit under two hours away. Cincinnati is about two and a half hours. Columbus is three hours. Chicago is a bit under four hours. Same with St. Louis. Detroit is five hours, and Milwaukee a few minutes more. Cleveland is five and a half. All of these cities are options for a day trip, and we’ve been doing our best to visit them all.

On trips to these cities, we’ve noticed that open country between them is part of what makes them cohere as a region: a feature rather than a bug— especially as the truck traffic between them gets thicker:

There is something new about all this.

What’s old are Designated Market Areas, or DMAs, also known as TMAs, or Televsion Market Areas:

These are (or were) defined by the collections of TV stations that households watched most. My company was once hired by the three major network stations in the Greenville-New Bern-Washington DMA to help pull viewers in Nash, Wilson, and Wayne Counties away from stations on the same networks in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill market. All stations on both sides had built 2000-foot towers to maximize their signals across overlapping counties. It was quite the war. (One we lost, but that’s another story.)

By now, TV watching has drifted from “What’s On” to “What’s Where.” And there are a zillion choices of “where”: everything on YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, on-demand subscription streaming services such as Netflix, HBO, Prime, Disney+, and your nearby cities’ TV stations. Inside that broad and growing mix, TV stations’ slice of the pie is smaller every day.

Regions now are defined more by commercial connections. Across transport “corridors,” forests and farmlands contextualize connected cities with wide rural frames. In McLuhan’s terms, the medium sending the message is the countryside flanking transport corridors between cities. I suspect this is true of all these megaregions, in different ways. Even the highly urbanized Northeast megaregion has lots of wild and open rural areas packed between their cities.

And what organizes the flow of all that commerce? Logistics. Which is digital, and for decades has been full of AI.

My thoughts on all this are just starting rather than finishing. I think a good place to do that together is by reading the study that got this started.

Leave a Reply to Doc Searls Cancel reply