Education 1.0 was about learning one one-on-one, or one one-on-few. Also by ourselves. This kind of on-site discovery and mentorship gave us stone tools, cave art, clothing, shelter, writing, engineering, construction on every scale, and great artists in every age. Writing was involved, mostly of the scribal kind before the Gutenberg Parenthesis began. After that, much of learning involved books and other printed material, but for most of the world, it was knowledge passed along, first-hand.

Education 2.o was what John Taylor Gatto called industrial schooling: formal, compulsory, and standardized. This is what we have had since the dawn of the industrial age.

Education 3.0 is what we get with Big AI, which will overthow Education 2.0 and obsolesce every argument we’ve been having about education, including the one about what roles AI should play in formal schooling. (Think of that last one as Education 2.9.)

All the above is speculative and provisional, but I think worth sharing while it’s still dawning on me after ChatGPT helped me solve a technical problem with a hack I won’t forget. Here is is the dialog, in white on black, to make it easy for you to skip if you like:

I wrote,

Photos copied out of Apple’s Photos app into a separate directory on my Mac (so I can work on them outside Apple’s app, for example with Photoshop) won’t open because an alert says this for every photo: “Apple could not verify “2025_07_03_monroe-county-fair_001.JPG” is free of malware that may harm your Mac or compromise your privacy.” Yet they have no malware. How can I bypass this alert and open the photos? Hitting the space bar on each file gives me a fine preview. But no app (not Photoshop, not Preview) will open them.

ChatGPT replied,

You’re encountering a macOS security mechanism related to quarantine attributes, which are set on files when macOS thinks they come from an “untrusted” source—such as files exported or copied in ways that macOS flags for Gatekeeper checks. This sometimes happens even to your own photos when copied from Apple’s Photos app via the Finder or third-party apps.

Background

The com.apple.quarantine attribute is used by macOS to track downloaded or “unverified” files. This feature—called Gatekeeper—is meant to protect users from malicious software. Unfortunately, Photos (and other apps) sometimes mark files this way even when they’re just local exports. Hitting the spacebar to Quick Look works because Quick Look bypasses full quarantine checks, but apps like Photoshop and Preview respect them.

Solution: Remove the Quarantine Attribute

Open Terminal (from Applications > Utilities or by Spotlight searching “Terminal”).Use the xattr command to remove the com.apple.quarantine flag from your copied photo files.If you want to remove it for one file:xattr -d com.apple.quarantine “/path/to/your/photo.JPG”Example:xattr -d com.apple.quarantine ~/Pictures/Exports/2025_07_03_monroe-county-fair_001.JPGTo remove it from all photos in a folder, run:xattr -d com.apple.quarantine /path/to/folder/*.JPG

Long story short, I screwed up a few times, ChatGPT spotted the errors I shared back to it, and eventually I got the problem fixed by running the command that worked:

xattr -rd com.apple.quarantine /Users/dsearls2/Pictures/pix-by-year/2025/07/2025_07_03_monroe-county-fair

Finally, ChatGPT added,

Quick Recap

Use Case Command to Run Clear a whole folder recursively xattr -rd com.apple.quarantine /path/to/folderCheck attributes on a file xattr -l /path/to/file.JPGRemove for a single file xattr -d com.apple.quarantine /path/to/file.JPGDisable quarantine system‑wide sudo defaults write ... LSQuarantine -bool NO+ reboot discussions.apple.com+12apple.stackexchange.com+12facebook.com+12

Now, would I have received the same help from an AppleCare call? Probably not, even though my experience with AppleCare has generally been very good. This was better, because I got schooled in an Eduction 1.o way.

That experience also got me thinking about the heuristics involved. So I engaged in further conversation with ChatGPT. Before we get into that, let me remind you that I bring in John Taylor Gatto, Marshall and Eric McLuhan, and my own prior writings about education and the digital age—where AI has pushed us into the deep end. (All those links go to stuff I’ve written on this blog. I’ve written a lot more about all of it elsewhere.) Here goes:

I said,

Okay. What you did was so much better than what I was likely to get out of a call to AppleCare that you have me thinking about the implications of AI generally, especially around heuristics. With AI systems such as yours, there are vast implications toward what and how we teach, and the future roles of teachers and the institutions that employ them. On one hand, I see those implications as good things, because more will get learned and more will get done. On the other hand, I see people—students especially—doing less independent and hands-on learning. Can you expand on those thoughts a bit?

ChatGPT said:

ChatGPT said:

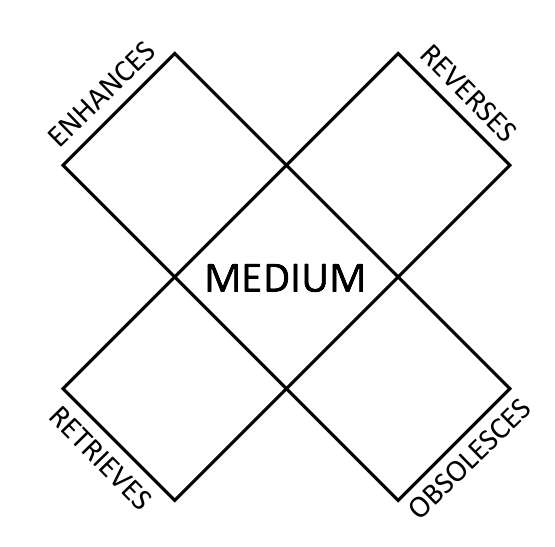

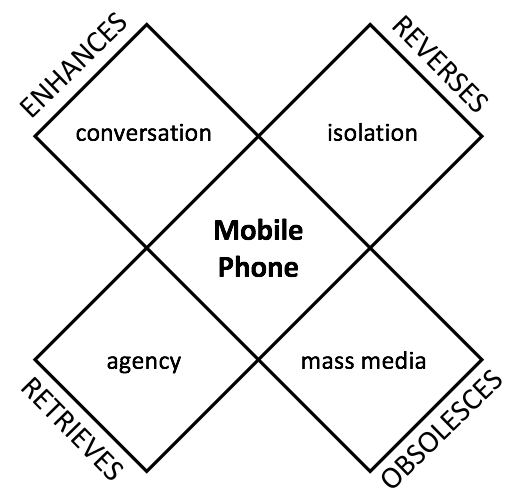

…along with examples of how the tetrad unpacks two media (or technologies, because to Marshall and Eric McLuhan, they are about the same) that are huge at this early stage of our new digital age:

…along with examples of how the tetrad unpacks two media (or technologies, because to Marshall and Eric McLuhan, they are about the same) that are huge at this early stage of our new digital age:

More about all that in What does the Internet make of us?

Now back to my conversation with ChatGPT—

ChatGPT said:

Leave a Reply to James Pasquale Cancel reply