Twelfth in the News Commons series

Last week at DWeb Camp, I gave a talk titled The Future, Present, and Past of News—and Why Archives Anchor It All. Here’s a frame from a phone video:

DWeb Camp is a wonderful gathering, hosted by the Internet Archive at Camp Navarro in Northern California. In this post I’ll give the same talk, adding some points I didn’t get to my 25-minute window. Here goes.

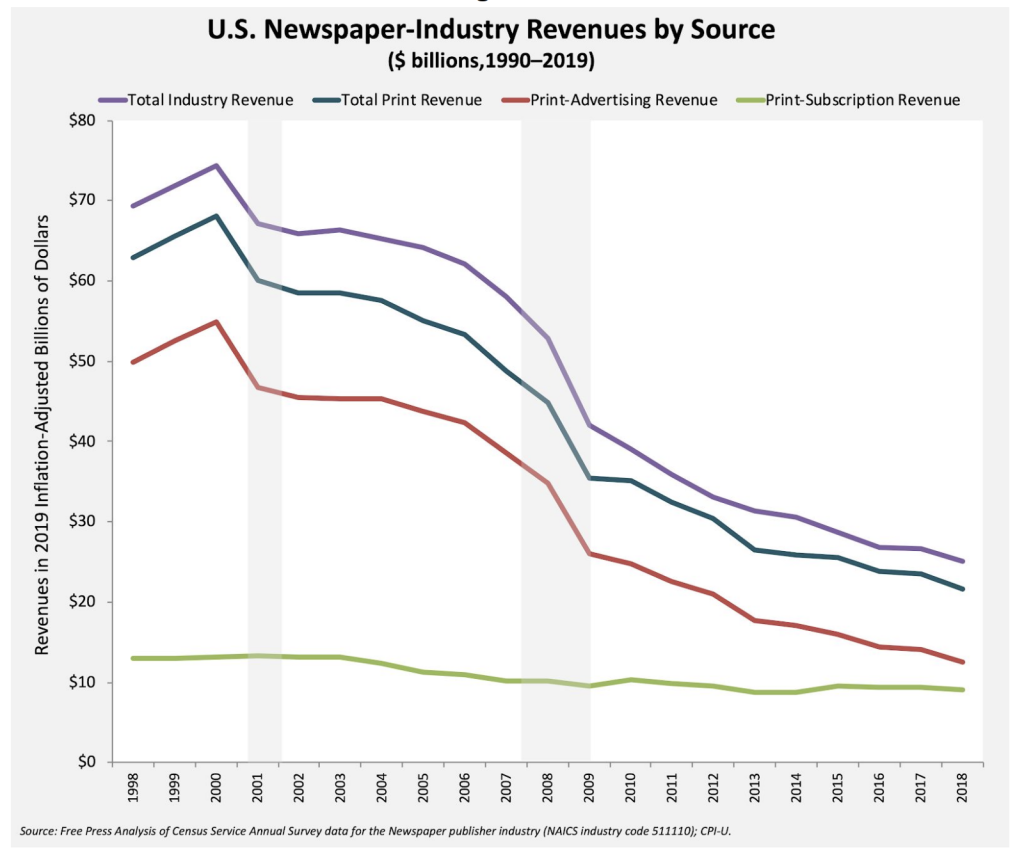

For journalism, news is bad:

Revenue sources are going away:

Wages suck:

So does employment:

But it’s looking up for bullshit and filler:

So what can we do?

There’s the easy choice—

But bear in mind that,

News only sucks as a big business.

But not as a small one.

For example, here:

Bloomington, Indiana. That’s where my wife and I are living while we serve as visiting scholars with the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University. I’ve lived in many college towns, and this is my favorite, for many reasons. One is the quality and quantity of journalism here. And that’s on top of what IU does, which is awesome. I speak especially of the IU’sMedia School, the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism, the Indiana Daily Student, or IDS (the oldest and one of the best of its breed), WFIU, WTIU, and the rest of Indiana Public Media. I mean all the periodicals, broadcasters, podcasters, bloggers, and civic institutions contributing to the region’s News Commons. I list participants here. (If you’re not on one of those lists, tell me and I’ll add you.)

Yet in 2017, Columbia Journalism Review produced an interactive map of America’s “news deserts” and made one of them Monroe County, most of which is Bloomington:

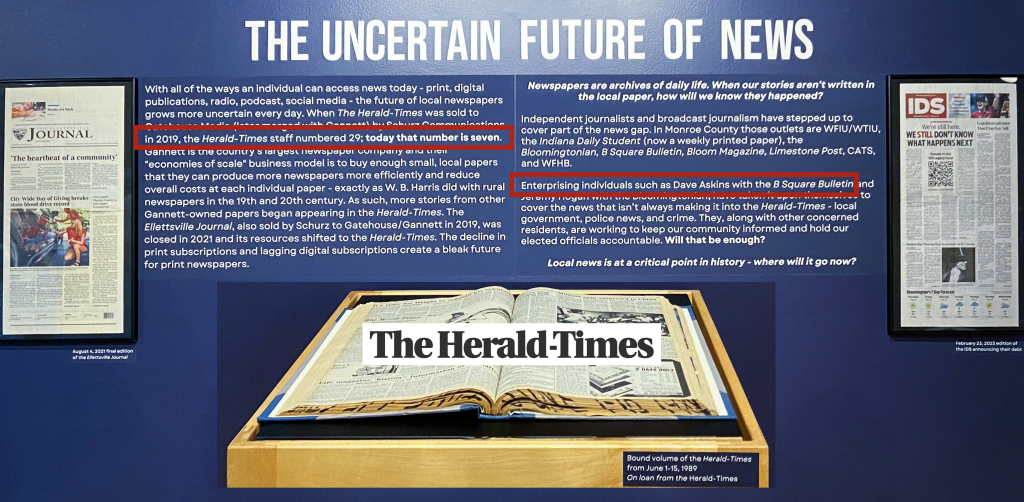

In fact, Bloomington did have a daily paper then: the Herald-Times. It’s still here in print and online. But, as “Breaking the News: The Past and Uncertain Future of Local Print Journalism” explained last year in a huge and well-curated exhibit at the Monroe County History Center,

the Herald-Times has shrunk quite a bit, while some “enterprising individuals” are taking up the slack—and then some. One they single out is Dave Askins of the B Square Bulletin:

Dave’s beat is city and county government. His “almost daily” newsletter and website are free, but they are also his business, and he makes his living off of voluntary support from his readers. More importantly, Dave has some original, simple, and far-reaching ideas about how local news should work. That’s what I’m here to talk about.

We’ll start with the base format of human interest, and therefore also of journalism: stories.

Right now, as you read this, journalists are being asked the same three words, either by themselves or by their editors:

I was 23 when I got my first job at a newspaper, and quickly learned that there are just three elements to every story:

- Character

- Problem

- Movement

That’s it.

The character can be a person, a ball club, a political party, whoever or whatever. They can be good or bad, few or many. It doesn’t matter, so long as they are interesting.

The problem can involve struggle, conflict, or any challenge—or collection of them—that holds your interest. This is what gets and keeps readers, viewers, and listeners engaged.

The movement needs to be toward resolution, even if it never gets there. (Soap operas never do, but the movement is always there.)

Lack any one of those three and you don’t have a story.

So let’s start with Character. Do you know who this is?

Probably not. (Nobody in the audience at my talk recognized him.)

He’s Pol Pot, who gets bronze medal for genocide, given the number of people he had killed (at 1.5 to 2 million, he comes in behind Hitler and Stalin) and a gold medal for killing the largest percentage of his own country’s population (a quarter or so).* His country was Cambodia, which he and the Khmer Rouge regime rebranded Kampuchea while all the killing was going on, from 1975 to 1979.

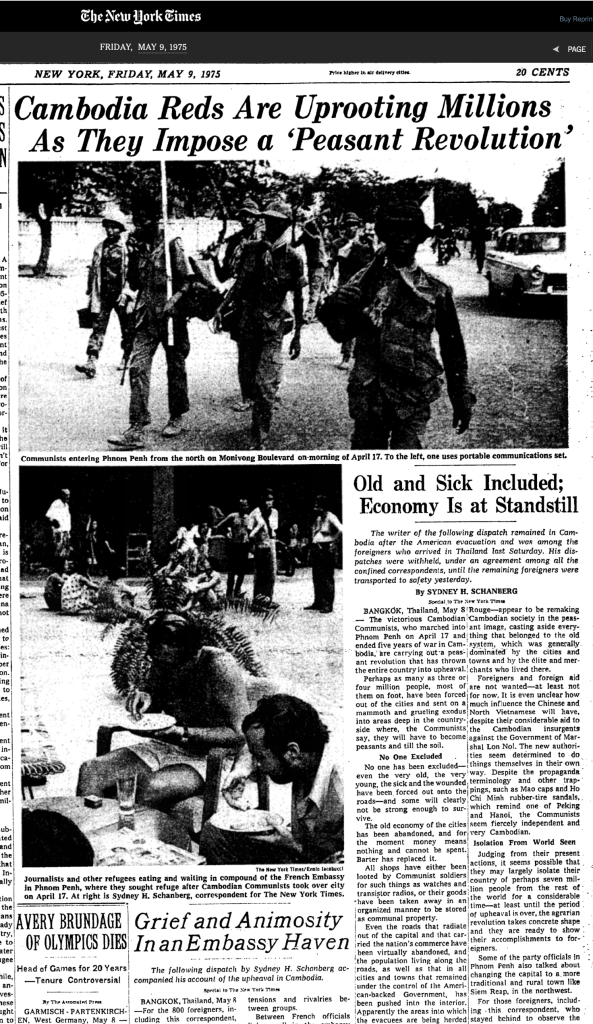

The first we in the West heard much about the situation was in the mid-70s, for example by this piece in the May 9, 1975 edition of The New York Times:

It’s a front-page story by Sydney Shanberg, who himself becomes a character later (as we’ll see).

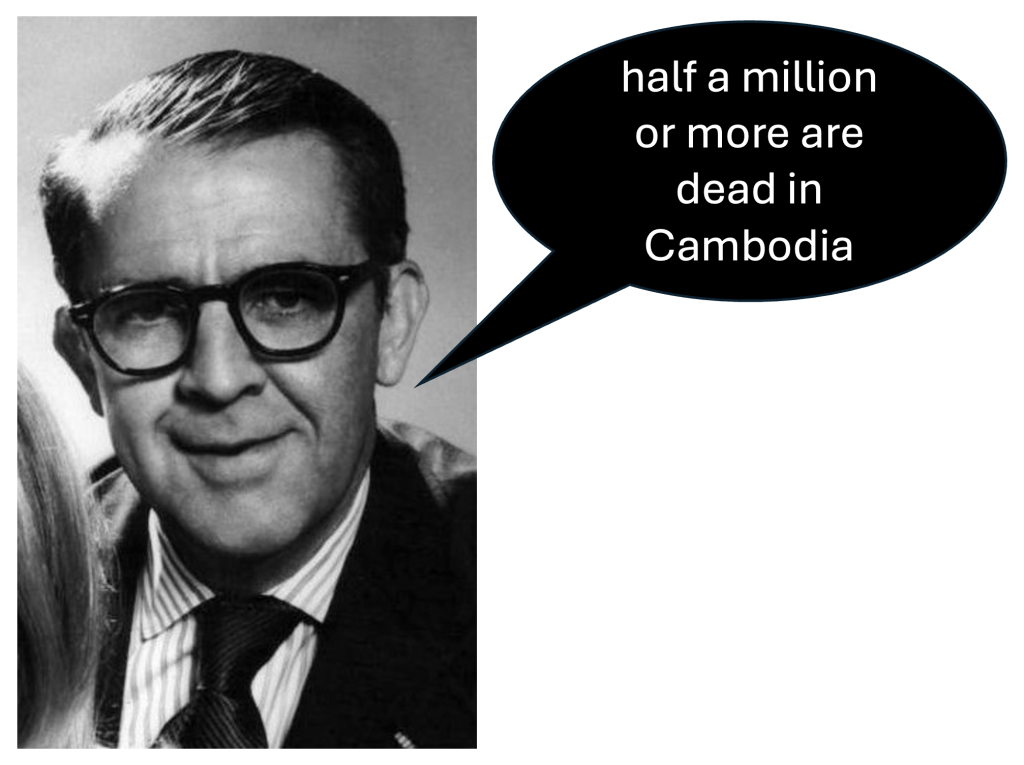

The first we (or at least I) heard about the genocide was sometime in 1976 or ’77, while watching Hughes Rudd on the CBS Morning News. He said something like this:

Wierdly, it wasn’t the top story. As I recall, it came before an ad break. It was as if Rudd had said, “All these people died, back after this.”

So I went to town (Chapel Hill at the time) and bought a New York Times. There was something small on an inner page, as I recall. (I’ve dug a lot and still haven’t found it.)

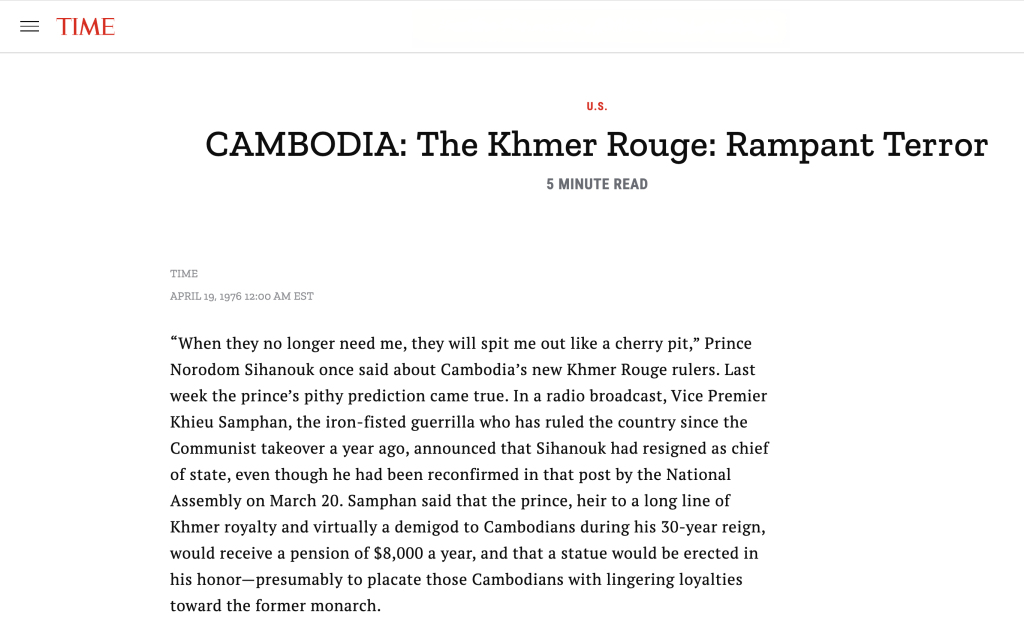

But Time, the weekly news magazine, did cover at least the beginning of the genocide, in the April 19, 1976 issue. (By the way, all hail to Time for its open archives. This is a saving grace I’ll talk about later, and much appreciated.) Here is how that story begins:

Note how Prince Norodom Sihanouk stars in the opening sentence. He’s there because he was a huge character at the time. (Go read about him. He was a piece of work, but not a bad one.) Pol Pot doesn’t appear at all. And the number of dead doesn’t show up until the following paragraph:

Imagine if one day every plane in the world crashed, killing half a million people. That would be news, right? There would be a giant WTF? or HFS! in the thought balloons over all the world’s heads. But, while the systematic murder of more than half a million people could hardly be a bigger deal, it wasn’t much of a story. Lacking a Hitler or a Stalin to cast in the leading role, Time borrowed some interest in deposed characters (Sihanouk and Nol) to pull the reader down to the completely awful news. But there were no journalists reporting from Cambodia at the time, and no news about who the dead people were, or who killed them. The whole place was a black news hole.

So, lacking the required story elements, news coverage of Cambodia in the late ’70s was sparse. Pol Pot didn’t show up in the Times until this was posted in the Sunday paper on October 7, 1977, deep in what might as well have been called the Unimportant section:

Note that “Top Spot to Pol Pot” gives more space to Cambodia’s military conflicts with neighbors than to the known fact that Pot’s regime was already a world-class horror show.

The Times‘ most serious coverage of Cambodia in those years was in opinion pieces. For example, an editorial titled The Unreachable Terror in Cambodia ran on July 3, 1978, and only mentions Pol Pot in the third paragraph. Holocaust II!, by Florence Graves, ran on Page 210 of the November 26, 1978 Sunday Magazine. It begins, “They don’t talk about extermination ovens or about freaky medical experiments or about lampshades fashioned from human skin. But the Cambodian refugees do talk about forced labor camps, about ‘deportations,’ and about mass executions.” Later she adds, “It’s a horror story which, for the most part, has gone unreported in the American press.” Because, again, it wasn’t a story.

But then this came, in January 1980:

In the opening paragraph, Sydney Schanberg writes, “This is a story of war and friendship, of the anguish of a ruined country and of one man’s will to live.” At last, we had a human being, and an interesting, sympathetic, and heroic character. His problem was massive, and the resolution was heartwarming. The whole story was so compelling that four years later it became one of the great movies of its time (with seven Academy Award nominations):

And, just as Anne Frank‘s story fueled greater interest in The Holocaust, Dith Pran‘s story fueled greater interest in the Cambodian Genocide.

Lesson: in story-telling, it’s hard for a statistic to do a human’s job. Another: that facts alone make lousy characters.

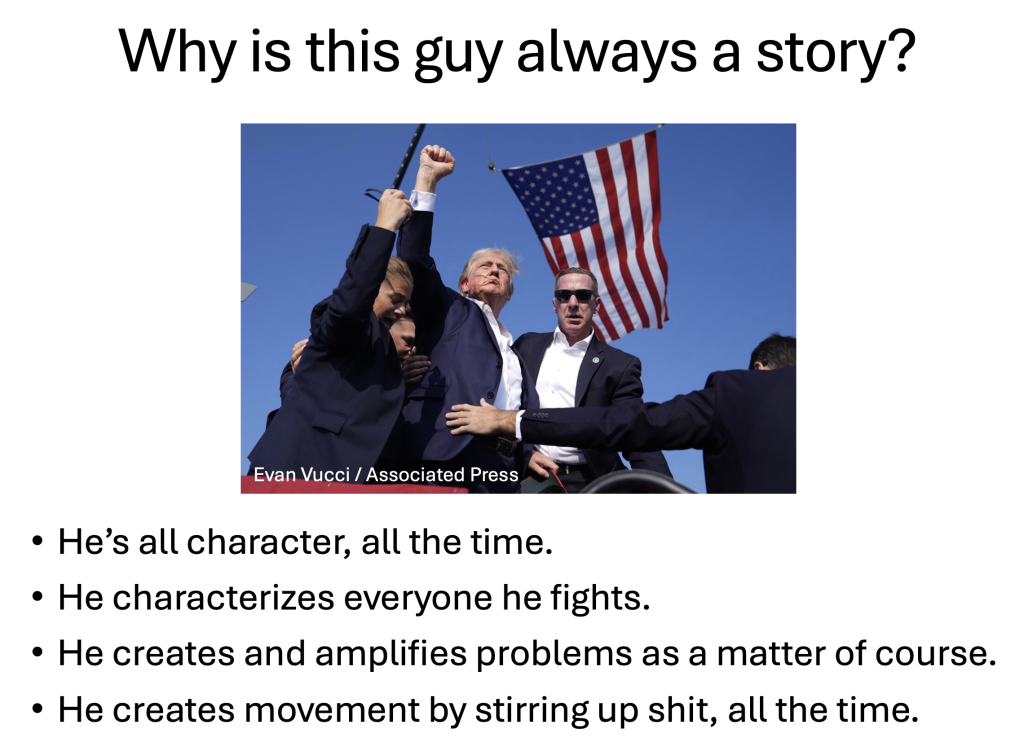

Now let’s go closer to home:

Trump is a genius at all that stuff. And he keeps his ball rolling by making shit up constantly. Think about it: you’re a lot more free to tell stories—and to move them along—if facts don’t matter to you. Also when your personal story transcends the absent truths in what you say. Trump’s story is a great one. Really. It is. He made himself one of the biggest (perhaps the biggest) and richest personal brands in the history of business and then got elected president by blowing through fourteen (14!) Republican primaries and caucuses and then winning the general election. As for why, here’s how I put it in Stories vs. Facts:

Here are another three words you need to know, because they pose an extreme challenge for journalism in an age when stories abound and sources are mostly tribal, meaning their stories are about their own chosen heroes, villains, and the problems that connect them: Facts don’t matter.

Daniel Kahneman says that. So does Scott Adams.

Kahneman says facts don’t matter because people’s minds are already made up about most things, and what their minds are made up about are stories. People already like, dislike, or actively don’t care about the characters involved, and they have well-formed opinions about whatever the problems are.

Adams puts it more simply: “What matters is how much we hate the person talking.” In other words, people have stories about whoever they hate. Or at least dislike. And a hero (or few) on their side.

These days we like to call stories “narratives.” Whenever you hear somebody talk about “controlling the narrative,” they’re not talking about facts. They want to shape or tell stories that may have nothing to do with facts.

But let’s say you’re a decision-maker: the lead character in a personal story about getting a job done. You’re the captain of a ship, the mayor of a town, a general on a battlefield, the detective on a case. What do you need most? Somebody’s narrative? Or facts?

The stories we tell depend on what we need.

Journalists need to fill pages and airtime.

Donald Trump needs to win an election. He needs voters and their votes. He’ll get those with stories—about himself, and about who he’d like you to hate along with him—just like he always has.

As characters go, Kamala Harris is a much tougher opponent than Joe Biden, because she’s harder for Trump to characterize, and she has plenty of character on her own.

And both make good stories simply because they both have character, problem, and movement. That’s why political journalism can’t help covering this presidential election as if it’s between equals, even though it’s not. (Trump has become ridiculous while Harris remains serious.) So Trump vs. Harris is a story. It has all the elements.

Things are different in places like Bloomington, where people live and work in the real world.

In the real world, there are potholes, homeless encampments, storms, and other problems only people can solve—or prevent—preferably by working together. In places like that, what should journalists do, preferably together?

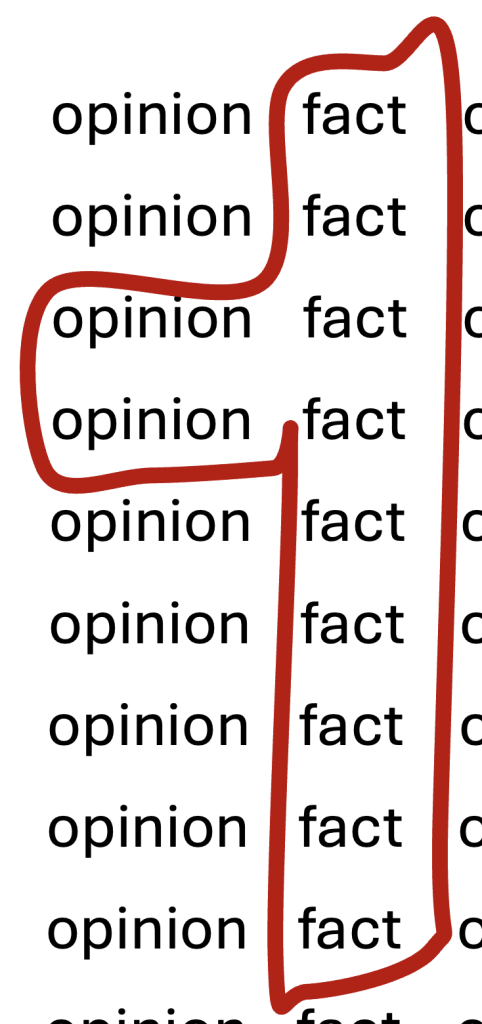

To clarify the options, look at journalism’s choice of sources and options for expression. For both, you’ve got facts and opinions. A typical story has a collection of facts, and some authoritative source (a professor, an author, or whatever) providing a useful opinion about those facts. Sometimes both come from the same place, such as the National Weather Service. So let’s look at different approaches to news against this background:

Here is roughly what you’ll get from serious and well-staffed news organizations such as The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, the BBC, and NPR:

Mostly facts, but some opinions, typically on opinion pages and columns, or in support of a fact-based story.

How about research centers that publish studies and are often sourced by news organizations? Talking here about Pew, Shorenstein, Brookings, Rand. How do they sort out? Here’s a stab:

Lots of facts, plus one official opinion derived from facts. Sure, there are exceptions, but that’s a rough ratio.

How about cable news networks: CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and their wannabes? Those look like this:

These networks are mostly made of character-driven shows. They may be fact-based to some degree, but their product is mostly opinion. Facts are filtered out through on-screen performers.

Talk radio of the political kind is almost all opinion:

Yes, facts are involved, but as Scott Adams says, facts don’t matter. What matters are partisan opinions. Their stories are about who they love and hate.

Sports talk is different. It’s chock full of facts, but with lots of opinions as well:

Blogs like the one you’re reading? Well…

I do my best to base my opinions on facts here, but readers come here for both.

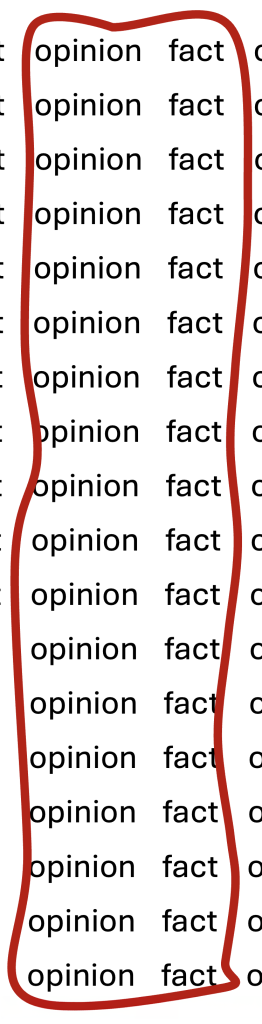

Finally, there’s Dave Askins. Here’s what he gives you in the B Square Bulletin:

Dave is about facts. And that’s at the heart of his plan for making local journalism a model for every other kind of journalism that cares about being fully useful and not just telling stories all the time. One source he consulted for this plan is Bloomington Mayor Kerry Thompson. When Dave asked her what might appeal about his approach, she said this:

Dave sees facts flowing from the future to the past, like this:

The same goes for lots of other work, such as business, scholarship, and running your life. But we’re talking about local journalism here. For that, Dave sees the flow going like this:

Calendars tell journalists what’s coming up, and archives are where facts go after they’ve been plans or events, whether or not they’ve been the subjects of story-telling. That way decision-makers, whether they be journalists, city officials, or citizens, won’t have to rely on stories alone—or worse: their memory, or hearsay.

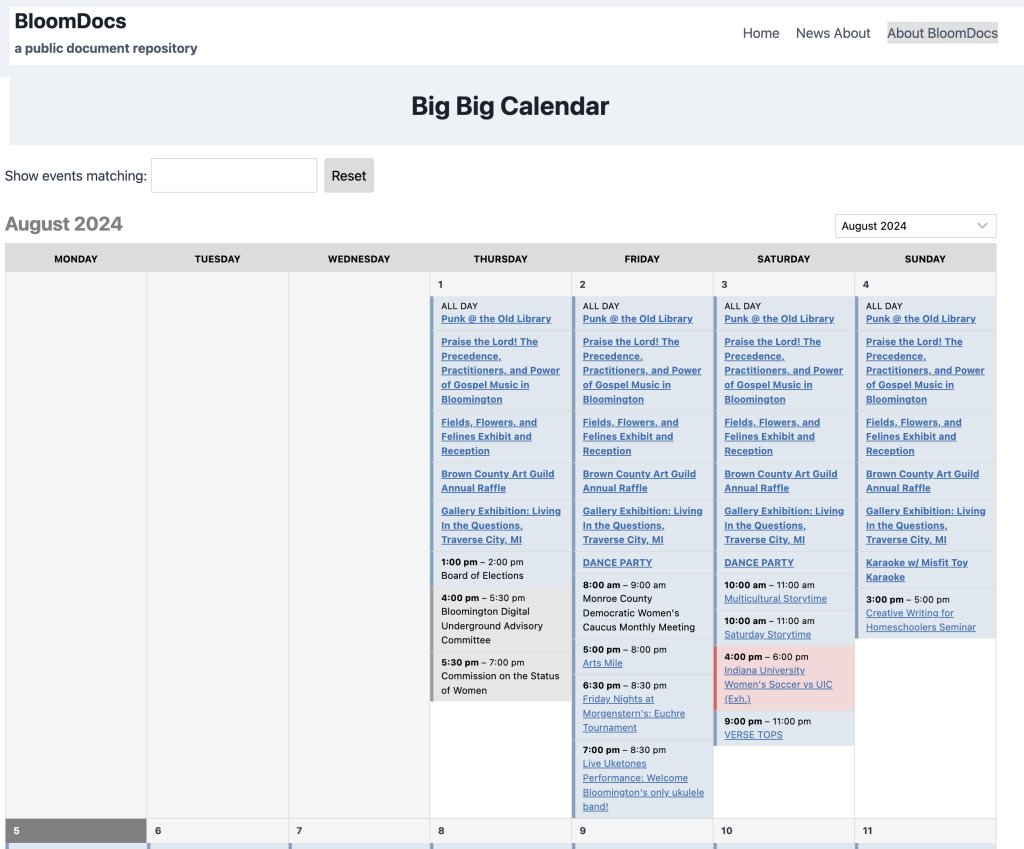

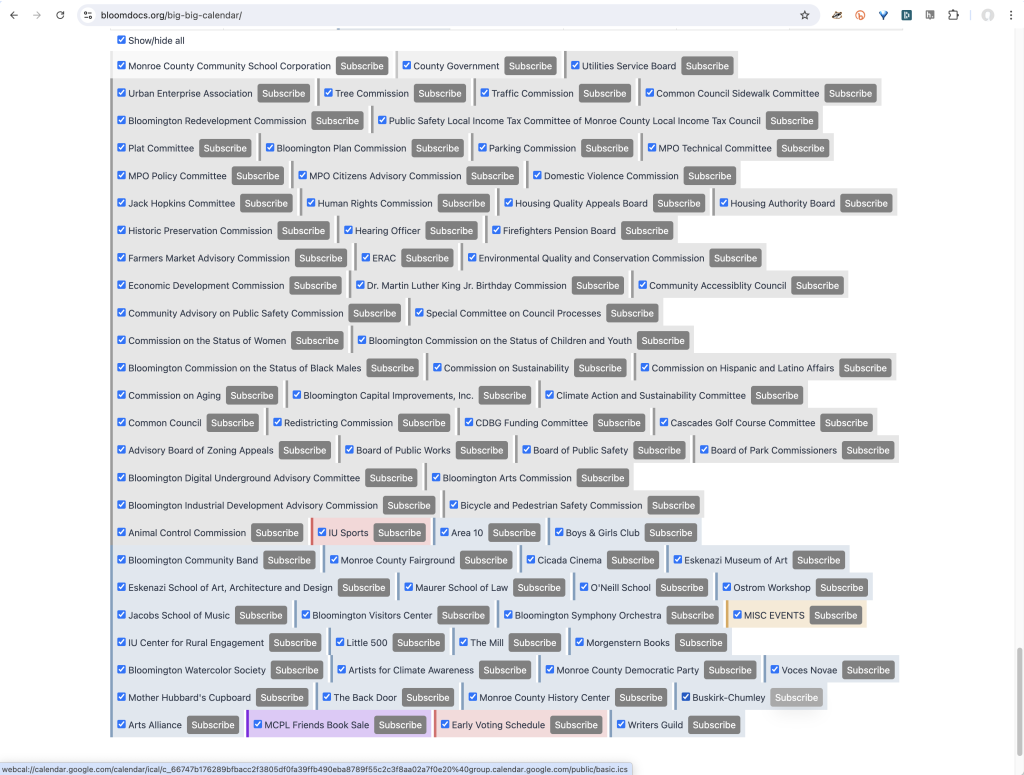

Dave has started work on both the future and the past, starting with calendars. On the B Square Bulletin, he has what’s called the Big Big Calendar. Here is how this month started:

Here are the sources for those entries:

Every outfit Dave can find in Monroe county that publishes a calendar and also has a feed is in there. They don’t need to do any more work than that. I suspect most don’t even know they syndicate their calendars automatically.

On the archive side, Dave has BloomDocs, which he explains this way on the About page:

BloomDocs is a public document repository. Anyone can upload a file. Anyone can look at the files that have been uploaded. That’s it.

What use is such a thing?

For Journalists: Journalists can upload original source files (contracts, court filings, responses to records requests, ordinances, resolutions, datasets) to BloomDocs so that they can link readers directly to the source material.

For Residents: Residents who have a public document they’d like to make available to the rest of the world can upload it to BloomDocs. It could be the government’s response to a records request. It could be a slide deck a resident has created for a presentation to the city council.

For Elected Officials: Elected officials who don’t have government website privileges and do not maintain their own websites can upload files to BloomDocs as a service to their constituents.

For Government Staff: Public servants who have a document they would like to disseminate to the public, but don’t have a handy place to post it on an official government website, or if they want a redundant place to post it, can upload the file to BloomDocs.

A future vision: “Look for it on BloomDocs” is a common answer to the question: Where can I get a copy of that document?

Dave also doesn’t see this as a solo effort. He (and we, at the Ostrom Workshop, who study such things) want this to be part of the News Commons I’ve been writing about here (this post is the 12th post in the series). In that commons, the flow would look like this:

All the publishers, radio and TV stations, city and county institutions, podcasts, and blogs I show there (and visit in We Need Wide News and We Need Whole News) should have their own arrows that go from Future to Past, and from Calendars to Archives. And when news events happen, which they do all the time and not on a schedule, those should flow into archives as well. We need to normalize archiving as much as we can.

Which brings us to money. What do we need to fund here?

Let’s start with the calendar. Dave’s big idea here is DatePress, which he details at that link. DatePress might be something WordPress would do, or somebody might do with WordPress (the base code of which is open source). I’m writing on WordPress right now. Dave publishes the B Square on WordPress. I’ll bet the websites for most of the entities above are on it too. It’s the world’s dominant CMS (content management system). See the stats here and here.

On the archiving side, BloomDocs is a place to upload and search files, of which there are hundreds so far. But to work as a complete and growing archive, BloomDocs needs its own robust CMS, also based on open source. There are a variety of choices here, but making those happen will take work, and that will require funding. Archives, being open, should also be backed up at the Internet Archive as well.

One approach is to fund development of DatePress and BloomDocs, and to expand the work Dave already leads.

Another is to drop the long-standing newspaper practice of locking up archives behind paywalls. (In Bloomington this would apply only to the Herald-Times). The new practice would be to sell the news (if you like), and give away the olds. In other words, stop charging for access to archives. Be like Time and not like the Times and nearly every other paper. This idea goes back a long way. Here’s the earliest example I can find. It was published on my old blog in 2006. Here’s another version published a year later. As I recall, Dan Gillmor and I were at one of many “save the newspapers” events when we came up with the sell the news and give away the olds idea. While digging around, I ran into Dan’s excellent book We the Media: Grassroots Journalism by the People, for the People, published in 2004. Re-reading it now, I realize that what Dan wanted then is exactly what the News Commons project is about now, two decades later.

Another is to look for ways readers, viewers, and listeners can pay value for value, and not confine thinking only to advertising, subscriptions, and subsidy. There are ideas out there for that, but I’ll save them for another post in the News Commons series.

What matters for now is that all the ideas you just read about are original, and apply in our new digital age.

These ideas should also open our minds toward new horizons that have been observed insufficiently by journalism since the word first entered popular usage in the middle of the 19th century.

The challenge now isn’t to save the newspapers, magazines, and TV news reports that served us before we all started carrying glowing rectangles in our pockets and purses—and getting our news on those. It’s to make facts matter and keep mattering after stories that use facts move off the screens, speakers, and earphones that feed our interests and appetites.

If you’re interested in weighing in or helping with this, leave a comment below or talk to me. I’m first name (well, nickname) at last name dot com.

*Based on estimates. Nobody knows for sure. Here’s Wikipedia.

Leave a Reply